Imagine for a moment that you a very lively boy, born into a

wealthy family where you

want for nothing. In fact, you’re so active and

bouncy, your mother says you are like a ball. You’re also spoiled and even bratty,

much learned from unquenchable, familial behavior. Intellectually, you are

amazing, picking up languages (Latin, Greek, French, English) very quickly and even

showing by three years old, a strong penchant toward drawing—something the entire family

does.

However, your mother is worried about you. You haven’t grown

as well as your cousins and other children. You are her only child; your

younger brother died just short of his first birthday from fever. Her relationship

with your father is strained. The match was wrong from the start. So you have

become the center of her universe.

Your father loves the outdoors and spends more time with his

horses, dogs and hawks than with you, that is, until you’re old enough to ride.

He thinks education is women’s work and he really won’t be part of your life

until later. Nonetheless, you idolize your father and he in return.

Then, at 14 you break the femur on your left leg and 15

months later, the femur on the right. Your legs never knit back properly and

you are damned to a crippling life never to reach higher than 4’11”. Your

mother pulls out all the stops, taking you all over Europe for a cure,

including the waters at Lourdes, praying for a miracle. In the meantime, your

father begins to distance himself. The hope of having his son by his side while

hunting and riding has been dashed. What’s worse as you head further into

puberty, your body and face change—you nose widens, lips swell with drool

coming down your tucked-under chin. Your torso grows, while your limbs stop

growing. All your relatives—cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents—begin to treat

you differently, not only a cripple but somewhat of a freak.

************

This was Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s early life. He was the product of first cousins and a

family that insisted on marrying within the bloodline to keep outsiders from

reaping from inheritances. What’s worse is his father was way over the top with

eccentricities: wearing a tutu to dinner, washing his shirts in the gutters of

Paris rather than trust a laundress to do the job right, doing whatever he

wanted, never caring what anyone thought or being a

notorious womanizer all his life. He once said that his women “did not mix love

into the matters of copulation.”

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Montfa was born in

1864 at the family home (they had several), Château de Bosc, in the town of

Albi. His father was Count Alfonse de Toulouse-Lautrec and his mother, Adèle

Tapié de Céleyran. Both families were among the oldest and most notable in

France, with a history dating back to the times of Charlemagne and the

Crusades.

Bedridden, while recovering from his injuries, Henri spent a

lot of his time drawing and water coloring. “I am alone the entire day. I read a

little, but after a while my head hurts. I draw and I paint so much that my

hand grows tired…”

His favorite subjects were horses, hunts, dogs.

While living in Paris with his parents, Henri was put under the tutelage of the

deaf-mute, Rene

Princeteau (1843-1914), a friend of the family. He and Henri got on very

well, some say that the infirmities they both endured helped to seal their

relationship. Neither whined about their problems, but instead

accepted their

fate and moved forward.

|

| Lost Self Portrait |

In time Henri moved onto the prestigious teacher, Léon Bonnat (1833-1922)

and when he closed his studio Henri moved over to the Atelier Cormon, an art school run by Fernand Cormon (1845–1924).

Cormon’s desire was to teach students so that they would end up in the

state-run Salon. Henri was to meet some of his closest friend there, including Émile

Bernard and Vincent Van Gogh. At the end

of the day though, he was tired of

learning about the traditional “Salon” method and wanted to venture out on his

own. “I am here to learn my trade,” he said, “not to let myself be absorbed.”

Henri began to frequent Montmartre —a section near Paris

that was incorporated as the

|

| Early Montmartre |

In 1881 Le Chat Noir

(the Black Cat) opened as one of the first cabarets (entertainment

|

| Moulin Rouge, late 19th century |

|

| Yes, they had a giant elephant in the garden where men would enjoy private belly dances and opium. |

Montmartre gave Henri a place to be. His monstrous looks

were often offensive to strangers and coughed up ridicule by others. Here, in a

world of other

outsiders, he felt safe. He was also frequently accompanied by

his friends for a protective purpose. He

had a lisp and drooled when talked and he waddled like a duck when he walked,

using a cane to help keep him steady. The only thing that seemed normal on him

was his big beautiful eyes. Conversely, he had a winning personality—never

showing pity for his plight in life (until the end) and was big on self-deprecating

humor (let them laugh with you, instead of at you). He was generous, caring,

passionate and sensitive. It sounds like he would have been a great friend, and

I believe that’s why so many of them stuck with him to the bitter end.

|

| At the Mouline Rouge Valentin dancing(background) |

|

| At the Moulin Rouge (1894-95) Friends visiting. Red head at table is Jane Avril,. May Milton is in the foreground. Notice the background. Henri is there! |

|

| Bal du moulin de la Galette (1889) Three prostitues looking for work as their pimp looks on. Compare this to Renoir's rending of the same place. |

Henri eventually set up a studio (after receiving an

allowance from the family) in Montmartre and a flat with his friend Henri Bourges,

who was a medical student. Even though influenced by artists like Degas and Bernard

at the time, he started to find his own way. He exhibited with the Impressionists,

the XX (the twenty) in Brussels and even had some drawings published in local papers.

|

| Poster advetising Jane Avril |

In 1893, his roommate moved out of their flat in order to

get married, Henri lost interest in Montmartre. By now he had contracted syphilis

and his roommate Bourges had been helping him as best he could medically (later

Dr. Bourges would write L'hygiène du

syphilitique in 1897). Henri turned to brothels.

As others would say, Henri felt like an outsider. His father

and family had rejected him, although his mother would stand by him to the end.

Beyond his physical difficulties, the family, especially his father found his

professional choice as an artist as offensive and demeaning. This was a world

beneath the privilege of his birth.

In turn, prostitutes were outsiders too. He ate with them,

slept with them, played with them (from cards to dice) and painted them. With

his deformed body, what better place to go than a place where the inhabitants

had seen everything! Nakedness meant

nothing to them either, making them perfect models. He once said, “Models

always look as if they were stuffed; these women are alive. I wouldn't dare pay

them to pose for me, yet God knows they’re worth it. They stretch themselves

out on divans like animals…they’re so lacking in pretention….”

Uniquely, Henri painted what he saw without comment. This is especially true with his album (series) of lithographs called Elles, where he depicted life inside a brothel. Here he shows women exhausted, waiting in line for their weekly checkup, caring for each other (many were lesbians, which fascinated Henri), bathing, waiting for customers and so on.

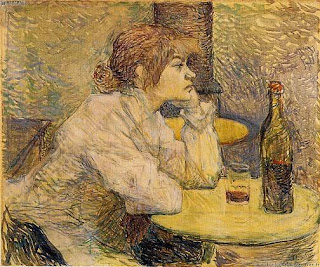

|

| Sketch for Hung Over |

|

| Hung Over (1889) |

Uniquely, Henri painted what he saw without comment. This is especially true with his album (series) of lithographs called Elles, where he depicted life inside a brothel. Here he shows women exhausted, waiting in line for their weekly checkup, caring for each other (many were lesbians, which fascinated Henri), bathing, waiting for customers and so on.

The drinking, fast-track living and syphilis finally caught up to Henri. Near the end, his friends worried about him dearly and with his mother’s help he was put into an asylum for detox. He hated it there because he didn't believe he was mad, just a drunk. He was extremely worried he would never see freedom again because, in his mind, it was risky to be a wealthy patient—the hospital loses the patient; they lose income. He indeed sobered up and began to draw circus motifs, all from memory!

Reluctantly, the doctors released him in May 1899. But by autumn, he was drinking again. At first, he hid his liquor in a small bottle hidden in his cane, but after leaving it behind during one of his trips, he just went back to his old ways.

|

| Two weeks before he died. |

By now, his production was considerably lower. He was only

in his mid-30s, but worse off than ever. These days he wasn't pleasant either.

All the pity, anger, resentment came out to anyone nearby. It as if a veil was

lifted, replacing all that good humor and cheer with his brokenness,

depression, rage and loss. Henri would live another 18 months, struck down by

paralysis (some say strokes) and the final stages of sphyllis. He was only 36 (a

few months shy of his 37th birthday).

Some call Lautrec, the chronicler of Montmartre, the soul of Montmartre, the master of lithograph, the first master of advertising design, the master of celebrity. All of this is true. Was he a saint? Not quite. Was he a master? Yes. But more importantly, he was a human trying to get through the day with far greater challenges than most of us have ever imagined. What sustained his life was drawing; it’s just unfortunate it couldn't have saved his life.

Next month: George Seura

What's Coming Up

See my www.jillgoodell.com for other details

New! Workshops at Glastonbury Studios

This summer I am trying out something new: holding one-day workshops in my studio, located in Tigard, just off highway 99. To ensure a high student-tech ratio, there is a minimum of five students with a max of ten.

The cost is $70 per workshop, which includes supplies and lunch. All you have to do is show up, ready to learn!!

Saturday, June 15

Let’s Draw! with Colored Pencils 10 a.m. To 4 p.m.

Learn how to use colored pencil by building up layers until you reach a brilliant, colorful surface. Learn how to use a variety of strokes and blending techniques. No experience needed. All supplies provided. Age 16+

Friday, July 19

Travel Sketching Workshop 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Journey with your sketchbook. Capture street scenes, markets, people and landscapes. Use pencil, watercolor washes or pen and ink. No experience needed. All supplies provided. Age 16+

Saturday, August 10

Let’s Paint! with Pastels Workshop 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Learn to create luscious pastel paintings using both soft and oil pastels on various papers and supports. Techniques covered will include:linear strokes, side strokes, blending, broken color, feathering, scumbling, sgraffito and stippling. May do some outdoor work in backyard if weather permits. No experience necessary. All supplies provided. Age 16+

To register for a studio workshop contact Jill at:

Glastonbury Studios:

Six-Week Classes Begin Week of June 2nd

Six-Week Classes Begin Week of June 2nd

Mark your calendars, the new classes for the first summer session will begin the week of June 2nd. I'm planning classes this time with similar themes: perspective, buildings and urban settings. Isn't it time to finally learn those pesky rules, so you can be confident when you're painting and/or drawing? Come see how easy it all is.

Tuesday evenings $70/session

7-9 p.m.

One, Two, Three Point Perspective

Come on, you know you should know this stuff. Perspective isn't as hard as you think. In fact, it can be lots of fun!! Will work from photos.

Wednesday mornings $70/session

10 to 12 noon

Sketch’n on the Go™

Urban Sketching

We will begin in the studio and as weather permits we will begin our outdoor sketch of the Portland Metro area for the summer

Thursday evenings $80/session

6:30 to 9:00 p.m.

Beginning/Intermediate

City Scenes

Let's explore different city scenes from Venice to New York and of course, our own sweet city of Portland. Learn how to embrace the city using classical structure, both day and night.

Second Sundays: Visual Journaling

1:00 to 4 p.m. No experience. $20

*********************************

For more reading on Lautrec see: http://www.courtauld.ac.uk/publicprogrammes/documents/toulouselautrecandjaneavrilteachersresource.pdf

Toulouse Lautrec, the Soul of Montmartre by Reinhold Heller (1997)

Toulouse Lautrec by Henri Perruchot (1960)

Lautrec by Edouard Julien (no date) knew the Lautrec family

Toulouse Lautrec by Henri Perruchot (1960)

Lautrec by Edouard Julien (no date) knew the Lautrec family

*Wikipedia definition: The use of the word bohemian first appeared in the English language in the nineteenth century to describe the non-traditional lifestyles of marginalized and impoverished artists, writers, journalists, musicians, and actors in major European cities. Bohemians were associated with unorthodox or anti-establishment political or social viewpoints, which often were expressed through free love, frugality, and—in some cases—voluntary poverty

No comments:

Post a Comment